Interview by Jennifer Walden, photos courtesy of Apple TV+; Dustin Harris. Warning: Contains some spoilers

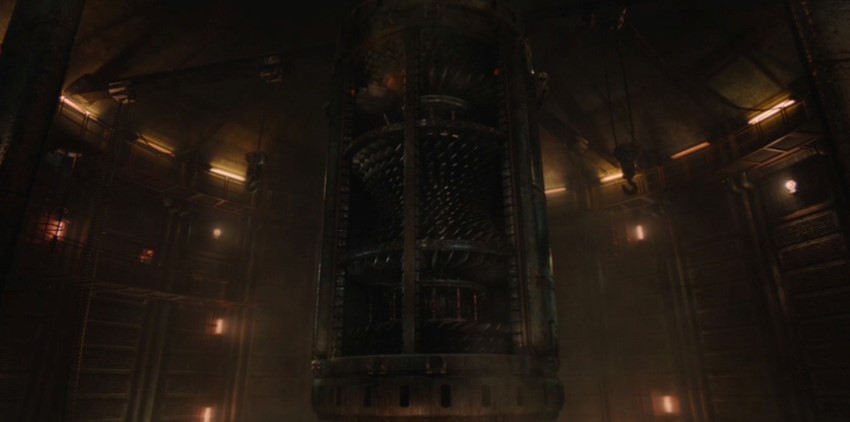

The season finale of Apple TV+ sci-fi/survival series Silo is coming this Friday (June 30th). In the show, a community of people created an underground society in a giant silo in order to survive the inhospitable environment on Earth. But life underground is restrictive and secretive. The citizens of the Silo are constantly monitored by Judicial, and information about the world outside is highly guarded by a few individuals. Links to the past – known as ‘relics’ – are illegal. But information (and the truth) can only stay hidden for so long.

Here, sound designer/supervising sound editor Nathan Robitaille and supervising sound editor Dustin Harris at Sound Dogs Toronto talk about creating the level-specific sound of life inside the Silo – from the Down Deep where shift workers maintain the life-supporting mechanical systems to the Up-Top where Judicial maintains order and control. They also discuss the sound of the generator (broken and fixed), using reverb and delay sparingly to help define the size of the Silo when appropriate, creating the sound of the outdated tech, being intentionally ambiguous with the sound of the world outside by playing with perspectives, using only non-wooden elements for effects and foley, and so much more!

Silo — Official Trailer | Apple TV+

What went into the ambiences for inside the Silo? As you get deeper into the Silo, how do the ambiences change?

Dustin Harris (DH): Right from the get-go, when Nathan and I saw the first cut and the rudimentary visual effects of the Silo, it already looked impressive and massive and huge. The first thing we thought was, ‘Oh man, we can do so much with reverb and delays.’

Sound supervisor Dustin Harris

Then Nathan quickly pointed out, ‘Why don’t we not do that, and instead, keep those in our back pocket?’

Because at first when you see the Silo, you want to hear all that stuff. But by leaving that out, we’re able to be more intimate with our conversations and we can better use the sense of space when we need to. When we do use it, it’s way more effective and the ear just doesn’t get used to hearing ‘Silo reverb’ all the time.

So we did make that choice early on to keep it pretty dry until those moments when we wanted to exploit it, like the Freedom Day Festival and Race to the Top. We could use those elements as new information for the ear to expose how big the Silo is.

Nathan Robitaille (NR): Reverb in a giant concrete silo can outstay its welcome pretty quickly. So we wanted to get ahead of it and have some control over how much of a presence it had in the show.

Reverb in a giant concrete silo can outstay its welcome pretty quickly.

Another big choice was to not lean so heavily on reverb when we went into flashbacks. This allowed the flashbacks to just be what they are. We trust the audience to know that we’ve gone back in time and are on a separate storyline. Dustin and re-recording mixer Steve Foster didn’t drench everything in reverb and I think that it cleaned up the show pretty nicely.

DH: Like all good sci-fi, the story is really about the people and what happens to our characters and their journey throughout the show.

When you watch the show, you get the sense that it’s a mystery at heart. A lot of the conversations that take place are quite secretive and very intimate. Having reverb in those moments would just highlight the space as opposed to the secretive nature of the conversations. The drier we can keep that, the more intimate and contained it feels. The dialogue lent itself well to that feeling.

…as we descend, a lot of our background conversations center around those things and daily routines.

The Silo itself has 3 distinct ‘neighborhoods.’ The ‘Up-Top’ are the administrative levels. It’s got a very governmental vibe, almost like the financial district of a city. Judicial is there. I.T. is there. The sheriff’s office there. The bureaucrats and heads of departments, along with their families live there.

Below that is called ‘The Mids.’ That’s where you find your suburbs, so there are families and a lot of 9-to-5 jobs and such.

Below that is the ‘Down Deep.’ That’s your shift workers, almost like factory workers and people that do a lot of physical labor. A lot of the infrastructure of the Silo is attended to in the Down Deep. The generator is there, repair shops, the main recycling sorting center, etc.. all that all happens down there.

So as we descend, a lot of our background conversations center around those things and daily routines. For instance, the Down Deep at night is still very busy because it’s 24/7 down there. There’s way more activity down there. For The Mids and the Up-Top at night, you virtually hear no background conversations or loop group because everyone’s asleep. We tried to really play with that idea of having traditional districts like you’d find in a city or a town except condense them into a silo.

NR: We supported all that on the sound effects side by honoring the physics of gravity. Dirt settles downward, so effectively the Up-Top would have a cleaning crew. They would have people sweeping the walkways and there are a lot of floor cleaners and things like that. But as you descend closer and closer to the generator, into the Down Deep, surfaces are dirty, and things are grimy. The knickknacks and gadgets and props that people use in their day-to-day life are a little bit worse-for-wear and so have a bit more sonic character. As you go deeper, you start hearing more texture under footsteps. In terms of foley, you start hearing more creaks on doors and a little bit more rust on some of the mechanical implements.

What went into the sound of the generator before it was fixed?

NR: The generator sound started with this placeholder track they were using in the Avid. It was actually a music track. I remember they were really happy with how well it worked, but it was an unusual music track. It had a lot of industrial, steampunk clinks and clanks in it as a rhythm section. It had these big, haunting horn risers that sounded like a metallic creature suffering. I think that’s what drew them to it. It worked really well for them.

…I started playing around with what I call the whale moans – these big, weird sounds that were coming out of the generator.

I wasn’t sure at that point what kind of music we were going to be getting from composer Atli Örvarsson. So I basically just went for the standard, industrial machine sounds, the rhythmic thumps and bangs, and things like that.

But then I started playing around with what I call the whale moans – these big, weird sounds that were coming out of the generator. That was fully inspired by the track that picture editor Hazel Baillie used in the Avid cut. The whale moans were largely resynthesized metal stress and contortion, and weird, strange, warping sounds. I fed those into a sampler and bent them out of shape.

To be honest, a lot of the other sounds that I built for the generator wound up getting stripped out because once Atli’s music came in, it was just so melodically beautiful that our sounds were stepping on its toes. So, piece by piece, we had to strip a lot of the details out. But what survived is what you would want to float to the top.

The workers have to repair the generator, so they remove these giant metal panels and expose the generator’s inner workings. A few of the blades are bent out of shape. The audience gets to hear the broken generator with the panels on, and then with the panels off (so the sound is no longer occluded by these giant panels). Can you talk about your sound design for the generator in this sequence?

NR: Dustin and I actually put ourselves in physical danger to get the exposed generator sound. That was a fun day.

DH: It just so happens that, as a hobby, I’ve gotten into metalwork these past few years so I have a lot of the tools that were actually used in that scene. When we got the cut, I said, ‘Hey Nathan, why don’t you come over and we’ll just drill stuff and bang on stuff and use the grinder and see what happens. Let’s just make some sounds.’

So Nathan came over with this heavy iron tube – a section of old plumbing stack or something.

Dustin and I actually put ourselves in physical danger to get the exposed generator sound.

NR: It was a plumbing stack that used to live in my basement. When that got ripped out of the house, I kept it because it sounds great.

DH: It’s like a foot in diameter and weighs about 50 pounds. So we put it up on a set of horses and started hitting it with everything I had. I have a five-pound sledgehammer and some axes. At one point, we connected some angle iron to a drill and we were hitting the pipe as this drill was spinning the angle iron around like a very dangerous windmill. It was a little sketchy.

NR: It was not safe.

DH: But it sounded cool.

NR: We should have a disclaimer saying that no editors were harmed in making the sound for this show.

DH: While it worked, it definitely wasn’t the smartest thing we ever did.

NR: Definitely not the smartest.

DH: But we were actually wearing safety gear.

Long story short, we got a bunch of metal and a bunch of tools and just started making sounds, breaking stuff, fixing stuff, and doing whatever we could just to get interesting, realistic metal sounds.

NR: I feel like that iron pipe should have its own IMDB page, with how many times I’ve used it in movies. It’s probably in most of the things I’ve worked on.

DH: It’s certainly worth keeping in your backyard.

NR: So that was basically the root of it all, and that gave us a lot of tactile presence. And then you add layers, you subtract stuff, and that’s the nature of the beast when you’re building larger, more complex elements like an open, running generator like that.

Tons of processing went into those layers but it all grew out of that one ridiculous session in Dustin’s garage…

In that sound, there are some other fun elements, like an AK 47 for some of those sparks. There were static jet whines that were run through an LFO to give it that rapid spinning sensation and wind movement that would be present around rotor blades spinning right in your face.

I did a lot of pitch-shifting. I love taking stuff that has a natively very high pitch and pitching it way down, or taking something that’s maybe slower and way lower and pitching it up just to separate it from its root source; it makes it a little harder to identify. There are elements in there that I’m sure you can identify if you’re listening for them. But there was plenty of pitching, and plenty of processing involved. Tons of processing went into those layers but it all grew out of that one ridiculous session in Dustin’s garage and it turned into a multi-layered monster of a broken machine.

And honestly, a ton of Kirk Lynds‘s magic is in there. He was mixing the sound effects on the show. When you show up with that many layers, you have to trust somebody to pick their moments and pick their tracks and sift through what is quite a wall of sound – to help settle on the right things to play at the right time.

In the show, they have to stop the generator in order to fix it, so you have the wind-down sound of the generator and then wind-up sound, too, when they get it running again. Can you talk about creating those sounds?

NR: That was just tedious. I think it worked though and really sounded great. I think we stuck the landing on the slow-down in particular. There is no wonder button that’ll do it for you. You can’t throw it through a decelerator or something like that. You have to get in there and cut it so that it sounds convincing and natural. Things slowing down and things starting up have a pretty distinctive sound to them.

So, it’s not just speeding up or slowing down; it’s really an evolution of sound throughout the whole process of accelerating and decelerating.

DH: There’s the instinct to assume you can take what you have built and either speed it up or slow it down, but it really does change overall. The mechanism and the physics of the whole thing just change on a moment-to-moment basis. Rhythms change, the relationships to the elements change, some things disappear as they lose energy, and some new elements show up. You have to build each moment of time as its own concept that is based on the concept that came before but evolves into a new thing. You continuously do that until the moment it ends. So, it’s not just speeding up or slowing down; it’s really an evolution of sound throughout the whole process of accelerating and decelerating.

NR: You’re cutting whoosh for whoosh at that point. I’m sure there are sounds I could have recorded, but to get that scale and have control over the pitch, to get the size of the rotors and respect the scale of what they had animated on screen, it was pretty important to get in there and just roll up the sleeves, get the hands dirty, and make it sound real.

After they fix the generator, it’s running smoothly, so you had to create a new sound for that. What went into the sound of the fixed and fully operational generator?

NR: I have to hand credit for that over to the director of that episode, Morten Tyldum. He had a very clear idea of what he wanted to accomplish with that wind-up sound. It had to be absolutely conspicuous that this thing is fixed. We get one chance to make sure the audience knows it. So, he was pretty involved in the whole process. With his direction, we got it exactly to where he knew it needed to be.

That whole sequence of them fixing the generator was action-packed and really tense! There’s incredible music and acting, and it makes for great suspense. What were some of your challenges in creating the sounds of the team fixing the generator?

NR: Really, we just had to get out of the way because the music Atli brought was so solid. It was very effective. With so much detail in a scene like that, it’s more important to ground yourself in the tension and the adrenaline of the moment and nothing can sell that as well as music. Atli absolutely nailed it.

With so much detail in a scene like that, it’s more important to ground yourself in the tension and the adrenaline of the moment…

We didn’t hear Atli’s music until much, much closer to the mix. Once we did, it became clear how we were going to make this feel pretty tense for the audience. A big part of building that sequence would’ve been Kirk and Steve trading moments at the mix desk, making decisions on when to pull out from the sound effects and give the music its space in the speakers in order to keep the energy up and keep this feeling as tense as possible.

When we see important story elements, like the red hot steam hatch, we’d play the creaks and warping sounds. Occasionally you’d hear the pressure build up and a bolt would fire out of a pipe and you’d hear it ricochet.

On the dialogue side, Dustin would have people yelling from the catwalk down to the scaffolding. We’d have tool sounds that poked through from time to time. But that fight was really won at the mixing desk. Kirk and Steve really worked their magic with the faders.

And to give credit where credit’s due, the acting in the scene was so superb.

DH: And to give credit where credit’s due, the acting in the scene was so superb. The amount of tension and urgency that actress Rebecca Ferguson (playing Juliette Nichols), actor Shane McRae (playing Knox, the head of mechanical), and actress Remmie Milner (playing Shirley, one of the engineers) had in their performances in that scene – capturing the feeling of the time crunch, and things steamrolling out of control, like the pressure rising too fast – help ramp up that sequence so much. So between them and Atli’s music, you have the core emotions of how the temperature is metaphorically and actually rising. Everything else is just busyness. The sound team provided that busyness of trying to get the job done.

NR: We provided the ear candy; we ornamented something that was already really robust.

As they’re fixing the generator, the Silo is running on backup power. When they shut the main generator down, the main lights go out and so does the screen with the view of the outside. But before it powers off completely, we see the screen flicker and the imagery looks green and lush for a moment. If there wasn’t a sound on the flicker, the audience might have missed it. Can you talk about your use of sound in that scene?

NR: The futz on that screen flicker was a game-day decision. Morten pointed out that if we don’t address that with sound, someone might not be looking. I don’t even remember what we used. It may have been something that Kirk pulled from somewhere else in the show, processed, and dropped in. It works for sure. It draws your eyes to the screen.

DH: It was a really cool and nuanced moment to shoot with our loop group because it’s a mixture of panic that the lights have gone out, and also an element of confusion because they have never seen the outside view look that way before. They don’t know what they’re seeing. It’s a really subtle emotion that you have to nail in a believable way so that it doesn’t sound canned and weird.

NR: Jack Madigan, who is our junior editor on the show, also ran with a lot of the crowd sounds as they hushed down and started realizing what was going on, and then react to the flash of green grass and blue skies on the screen. Jack really brought a lot of life to that scene as well.

I’m a big fan of lightbulb sounds and the sounds of lights flickering or turning on and off. In this generator power-down sequence, the lights go out, level by level, in the Silo. It sounded great! What went into that?

NR: Craig MacLellan was the sound effects support editor on this show. He absolutely knocked it out of the park with all of the details like the light sounds. We had a conversation early on about how those should feel. (I feel the same way about lights as you do, Jennifer. I like them to sound musical, delicate, and glassy.) He ran with it and I was thrilled with his results. I love the elegant subtlety of all those little details.

The sequence where they turn off, level by level, was one of those beautiful sequences that really show you how quiet scenes can be as difficult to build nuance into as louder more complex scenes. We really have to choose our sounds wisely when there is nothing to hide behind.

I love the sound of the outdated technology in the Silo, like Martha sitting there tinkering with broken gadgets, and in George’s shop, they recover data from the ‘relic’ drive. What went into the sound of the computers and their interfaces? Were you able to record some old gear to get those tactical sounds? Foley? What about the computer GUI sounds (we see/hear it as Robert investigates the pez relic)?

DH: It’s so cool from a nostalgia standpoint. The Silo has this post-war, brutalist aspect to the design language, but then you’ve got this computer equipment that seems early ’90s except the screens are 1:1, which is a really interesting aspect ratio.

NR: The sound of the computers is a two-component epoxy. Because of my dad’s work when I was a kid, there were a lot of early-stage personal computers at my house and I remember what they sounded like with those massive floppy discs, weird, crunchy access sounds, and wild servos. My childhood memory of computers as physical machines made me want to focus on their physical presence and that was the first component.

Atli’s voice feed had this really crazy digital purring sound. I remember listening to that and saying, ‘Oh man, it sounds like Judicial is listening in.’

They also sounded like they were breathing when they were on and idle. This show seems to play games with our sense of trust and paranoia so I wanted that to be a part of these computers, almost as though they‘re listening to you. In an early spotting session – the first one that Atli joined us for – for some reason, Atli’s voice feed had this really crazy digital purring sound. I remember listening to that and saying, ‘Oh man, it sounds like Judicial is listening in.’ I grabbed my Zoom H6 recorder and (while Morten was taking another call) I recorded some good clean purring from my speakers. It had a really sketchy surveillance vibe to it so I named it the “Atli purr” and it became part of that physical component.

The second component was the GUI sounds. In the Avid, they needed to convey that the computers should sound innocent, pleasant, and inviting. The funny thing is that the chimes and sounds they used as placeholders were Windows XP sounds, and this is an Apple TV+ show, so we certainly couldn’t use those. But they needed to nod to the comforting swooshes, chimes, and piano glisses from that era.

I listened to a lot of very simple mid-late 90’s to early 00’s OS sounds. The simplicity requirement definitely added a challenge.

They can’t be too hi-fi because that doesn’t exist in the ‘Silo’ world, which is very much stuck in the ’90s and before.

DH: To Nathan’s credit, one thing I loved about those computer sounds so much is that the old ’90s Windows XP sounds have this graininess to them because the system could only support 8-bit/11 kHz sounds. Nathan was able to get that really grainy sound to them. It was perfect. They can’t be too hi-fi because that doesn’t exist in the Silo world, which is very much stuck in the ’90s and before.

NR: Thank you! Most of those sounds were made with basic, stock MIDI instruments – the ones that you typically avoid because they don’t sound very natural. Then, I tried to make really simple, iconic, pretty little melodies out of them. I handed them over to Kirk at full frequency and the rest of the magic happened under his fingers. He processed them and squeezed them into the box on-screen so they felt like they were coming out of that computer. I thought it worked beautifully.

During Holston’s walk up the stairs to the outside, how were you able to use sound to convey his uncertainty and trepidation in that scene? (I love the sound of the big door opening up to outside).

DH: The setup for that actually starts in Ep.1. When Allison goes out to clean, we made a very conscious decision that once her helmet was on, we didn’t hear her anymore. The Silo residents and the audience alike were cut off from her and don’t know what her experience was like at all, aside from what we saw on the screen. The reason that is important is because when Holston goes out, he and the audience are both experiencing the outside for the first time. It was important that the audience is just as unfamiliar with it as he is.

It was important that the audience is just as unfamiliar with it as he is.

All of the sounds of him were actually recorded in the suit on the day, which is fantastic. We cleaned them up because there is the classic issue that you get with a helmet scene – they have to have a fan in there to keep the visor from fogging up, and they’re usually noisy and have a motor whine and such. So we cleaned that up and got it out of the takes. What actor David Oyelowo (playing Holston) did on the day in the suit was awesome. All of his efforts and everything just sounded so authentic. We did put his breaths and efforts on the ADR sheet anyway, just to cover it in case we needed more, but once I cut the sequence and showed it to Morten, he didn’t want to shoot ADR for it. All of David’s sounds were superb. So we went with what he did on the day and it was perfect.

NR: His nervous breathing as he walked up that ramp was priceless. That was beautiful.

All of David’s sounds were superb. So we went with what he did on the day and it was perfect.

On the sound effects side, we followed the same perspectives, whether it was playing the dulled, out-of-body experience of Holsten’s shock as he watches Allison go out, or the visceral, first-hand experience of going out with Holston. Craig built those big airlock doors and mechanical elements in a way that allowed us to deliberately play them from very different perspectives. It could play in the room; it could play subjectively, or it could play through a helmet. It was just a matter of following those same perspective cues so that the audience could experience that with the characters on screen.

Holston’s view of the outside was surprising! What went into the sound of the world outside? What did the showrunners want the audience to hear when people went outside?

NR: The direction was to be deliberately ambiguous. They wanted it to be up for interpretation yet it was very hands-on – they told us when to hear bugs, birds, and wind in the grass and when we should overwhelm reality with music and sound design. It was all designed to leave the question in the audience’s mind.

DH: This is a mystery that goes to the very last second of the season.

Popular on A Sound Effect right now - article continues below:

We talked about this a bit earlier in the interview, about choosing the moments to use reverb creatively and as a storytelling tool. I love that you did that in The Race to the Top. Juliette is hanging over the rail and you hear the people yelling, ‘someone save her!’ Those yells ring out in that stairwell space. Can you talk about that sequence?

DH: Reverb had a really important role for that sequence because the Silo, as you see in the wider shots, more or less looks the same from the central column – all of the stairs have the same design. It’s one giant set of stairs from bottom to top. Since it all looks the same, we had to rely on sound to tell us where we were in the Silo at any given moment.

…people cheering the racers have a different emotional energy to the confused and hassled bystanders watching Juliette chase Trumbull.

In The Race to the Top, we start in two different places. The racers start from the bottom and work their way up, while Juliette is chasing Trumbull from the top going downwards, and eventually, the race has a head-on collision with the chase. So we had to pick different sonic flavors in terms of what the crowd was doing, and what they were responding to. Those flavors had to tell us which story we were telling at any given point, for instance, people cheering the racers have a different emotional energy to the confused and hassled bystanders watching Juliette chase Trumbull.

By alternating between those perspectives, we were actually able to create separate spaces that eventually merged into one.

Once the action stops switching perspectives and we stay with Juliette, you can still hear the race going on above and below because you hear these crowd bursts as other groups of racers are going by each level, but the crowds surrounding the scene of Juliette dangling from the railing have that confusion and concern.

NR: I might have received my favorite note ever from executive producer Graham Yost on that sequence; it came through Ben Brafman, our post producer. Graham referenced downhill mountain bike races. If you’ve ever watched one, you’ll know that the spectators stand in groups along the trail, and as the mountain biker comes down the mountain, you’ll hear people way in the distance blaring horns and making noise. As that mountain biker gets closer, so do the groups of people cheering them on. This continues as the rider passes you and the groups recede into the distance down the mountain. Graham wanted The Race to the Top to feel like that.

We were all recording these elements to help bring that to life and help the audience feel like they were part of the race.

I’m an avid mountain biker, and so I’ve heard that sound a million times. I love all the Hooliganism and spirit at those races. As soon as I got that note, I got on the phone with both Jack and Craig so all three of us could cover it as a team. Craig bought a bunch of noise makers from Amazon, gave them to his kids, and recorded the mayhem. I started making all these Doppler versions of cowbells, vuvuzelas, and other noise makers to support the speed and pace of the race. Jack did the same thing. We were all recording these elements to help bring that to life and help the audience feel like they were part of the race.

What’s been the most challenging episode so far for sound? Why? What went into it?

NR: I don’t know that it’s really one episode specifically, but rather a concept that wraps all the episodes together. The most challenging thing – and this applies to foley, sound effects, dialogue, everything – is that there’s no wood in the Silo. So, the fact that if a door had any elements that even had a resonance that reminded us of wood, it had to go.

Craig had to build this massive library of creaky metal hinges that weren’t connected to doors that resonated like wooden doors.

Craig had to build this massive library of creaky metal hinges that weren’t connected to doors that resonated like wooden doors. Foley couldn’t use props that sounded like wood, even if they weren’t wood. Everything had to sound like concrete, glass, metal, and engineered material. But wood in the Silo has the same value as diamonds because trees in the Silo are too valuable for their fruit to be cut down and used for wood. And so there are only a few wooden items in the Silo, like the door to Holding Two is wood, the mayor’s desk set is wood, and the judge’s desk and door are wood.

Those are things that were defined for us for the first episode. So we weren’t allowed to touch wood outside of those elements. Subtracting an entire group of material from your sound editorial palette presents real challenges. Those kinds of interesting, creative, deliberate limitations were what made the whole series a bit more challenging.

Any lines that had hollow footsteps on them, if we couldn’t clean it up, we had to shoot ADR to get that wooden sound out.

DH: We ended up shooting some ADR, particularly when people are coming into their apartments or leaving, because all of those steps are just hollow plywood (it’s a film set). Any lines that had hollow footsteps on them, if we couldn’t clean it up, we had to shoot ADR to get that wooden sound out.

NR: And we’d have to shoot foley for that because we couldn’t use the production effects.

DH: It’s a deep concept in the show, that aside from the wooden accents Nathan mentioned above, all of the materials in the Silo are intentionally reusable materials. So everything’s metal, concrete, etc. Going to recycling to get and give items happens a few times throughout Season 1.

NR: Steve Baine and Peter Persaud – our foley team – had their hands full with that, and they nailed it. It’s crazy how many times you record something and when you listen to the recording through headphones, it may sound like wood even when there was no wood used. If it sounded like wood or sounded wooden, we had to get rid of it.

John Mooney, the production recordist, did a fantastic job.

DH: John Mooney, the production recordist, did a fantastic job. He used the Schoeps SuperCMIT, which was new to me. It’s a digital microphone with some DSP onboard, and the idea seems like it is a mid-side microphone, but instead of using the side information to give you a stereo field, it takes that information and subtracts it from the mid signal. Effectively what you get is this boom track that is super dry, with no off-axis information whatsoever. You just get what you’re pointing it at and nothing else. It was super cool.

John and his production sound team were so on top of it because it’s a very directional microphone and they always had it pointed exactly where it needed to be. I think it was a smart choice for this show because when they built the ‘Silo stairs’ set, it is three entire levels, so there is always a ‘practical’ level above and below the shot before CG is added. It’s a gigantic set, but it’s all plywood. None of the dialogue could sound woody. It couldn’t have that resonance or that space to it that suggests a wooden set. And John and his team absolutely tamed it and nailed it.

What are you most proud of in terms of sound on Silo?

DH: I love the sound of the dialogue on this show! I’m really motivated by people who say they ‘can’t understand the dialogue on shows these days,’ and I think on this show we had that goal in our sights. The dialogue in this show is usually quite intimate, almost like every conversation is a secret… So how do you get that clarity and still allow the outside world in, but still have it feel intimate? It starts with good ingredients, and John Mooney delivered it on the production side. His resume speaks for itself. He’s a wonderful person and delivers superb tracks.

Krystin Hunter, our dialogue editor, is a genius at repairing words and syllables with outtakes.

I’m truly lucky to have the team I have on this show…

I’ve also worked with Steve Foster, our dialogue and music re-recording mixer for years, and we have a really similar approach and idea of how we like things to sound.

I’m truly lucky to have the team I have on this show because it makes my work look so good. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the wonderful ADR mixing Goldcrest London did with us this season as well. ADR mixing is a skill and talent all its own, and it has little to do with running Pro Tools.

NR: I’ll tell anyone who will listen about how amazing Craig MacLellan and Jack Madigan are. The same goes for Kirk Lynds, our effects re-recording mixer, as well as Steve Baine and Peter Persaud in our foley department. It really does come down to having killer ingredients and an amazing team. I couldn’t be happier with all of it.

A big thanks to Nathan Robitaille and Dustin Harris for giving us a behind-the-scenes look at the sound of Silo and to Jennifer Walden for the interview!